Q&As

- Share funds v rental property.

- Income splitting by the self-employed — is it OK?

QYour position regarding share market (via unit trusts) versus property investment is well documented. My own personal situation has proven the exact opposite.

Over the last five years I have contributed $59,000 into a unit trust scheme managed by Bankers Trust. Three months ago I received notification the fund was closing.

Members were given the option of withdrawing from the fund. I received $61,000.

How do you equate a $2000 net return over five years against returns enjoyed by those in the property market?

Am I justified in feeling a little cheated and let down?

AI would be interested to see this documentation on my position!

It should start with five basics:

- Over the long term, shares tend to bring higher average returns than property. This is because they are riskier, and higher-risk investments on average have higher returns.

- You can raise your risk and expected return in either shares or property by borrowing to invest — sometimes called gearing.

- You can reduce your risk without reducing your expected return by investing in a large number of shares or properties. If some do badly, there’s a good chance that will be offset by others’ doing well.

- When I say “expected” return, that’s the average of long-term returns on that type of asset. But actual returns range from huge gains to huge losses in both shares and property.

- Investments in either should be for the long haul, preferably ten years or more. Over a shorter period, there’s a fair chance you will do worse than in the bank or even lose money.

There’s no denying that some people have done fabulously with recent property investments.

But, while shares are basically riskier than property, the typical New Zealander’s property investment is probably riskier than the typical share investment.

Most people buy just one rental property. What’s more, it’s often a house near their home, which further reduces diversification. Also gearing, via mortgages, is much more common with property than shares.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when inflation was high and the value of most investments rose fast over time, gearing wasn’t nearly as risky as now.

But, despite big recent house price rises — or perhaps because of them — it’s highly likely that prices will fall some time in the next ten years, just as they did during three periods in the 1990s.

People with mortgaged properties might find they owe the bank more than their property is worth, when they have to sell. It’s happened elsewhere.

What about shares?

It’s much easier to diversify in shares than in property. You can make a small initial investment into a unit trust or other share fund, and also make ongoing contributions, as you have done.

The type of share fund you have invested in is not what I would recommend. I prefer index funds, which invest in the shares in a market index, largely because they are cheaper to run so their fees are lower. That makes a big difference to returns over the years.

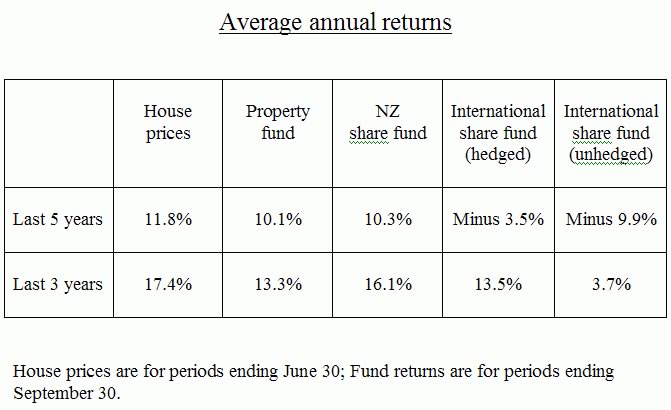

Still, even index funds in overseas shares have performed abysmally over the last five years. For example, the average annual return on SuperLife’s hedged overseas index fund is minus 3.5 per cent. And on its unhedged overseas fund it is minus 9.9 per cent. (All the SuperLife returns include dividends and are after fees and taxes.)

On the other hand, SuperLife — which runs a super scheme for individuals or employees — reports a healthy five-year average annual return on its New Zealand index fund of 10.3 per cent.

This beats 10.1 per cent on Superlife’s property fund, which invests in local and overseas commercial, industrial and retail property.

And it’s not all that far behind house prices, which rose an average of 11.8 per cent, according to the QV house price index.

Note: The 11.8 per cent doesn’t include rental income, but nor does it allow for property expenses, all of which vary widely. Suggestions on how to allow for that are welcome. Meantime, we’ll just use the capital gain numbers.

What about the last three boom years, when the QV house price index rose an average of 17.4 per cent a year?

The rising kiwi dollar meant SuperLife’s unhedged overseas share fund still managed only 3.7 per cent a year. But the hedged overseas fund reported a strong 13.5 per cent a year, and the New Zealand share fund 16.1 per cent — outdoing the property fund’s 13.3 per cent.

Again, houses beat shares but not hugely.

In any case, five years is too short a period to judge, and three years is even sillier.

If I were you, I would invest the $61,000 in several index funds — New Zealand and overseas — and give yourself a ten-year horizon.

Even then, you might still find property would have been better. There are no guarantees. But I’ve got my long-term savings in index funds.

By the way, your return is not quite as dismal as $2000 on $59,000 over five years. The full $59,000 wasn’t invested for five years, as you drip-fed it in over the period.

Still, it is terribly disappointing. Whether or not you have the courage to stick with share funds in the future, I wish you many happier returns.

QYour recent comments on income splitting between spouses are sound, and I do not disagree with you. However, one tax anomaly which you and every other commentator fails to mention (or realise?) is the tax benefit available to self-employed “couples” but not couples where one is employed and one is at home with children.

My brother-in-law owns his own business. He annually pays through the company accounts $20,000 to $30,000 to his wife as an “employee”. She would be lucky to be licking a few stamps, if anything.

But this is perfectly legitimate, and hence he legally “splits” at least $20,000 to $30,000 of his income this way, his wife paying a much lower tax rate on that amount.

Such “income splitting” is not available to me as an employed person, with a home executive wife. I pay full tax on all my earnings, and my wife pays no tax as she has received no income.

This is an unfair tax advantage that is routinely abused by thousands of Kiwis. (I am a lawyer so I can say that with some credibility).

Just a comment to add to this important debate.

AI could get snippy and say that I did go into this issue last year in this column. But let’s concentrate on the important stuff.

What your brother-in-law is doing is not “perfectly legitimate”. Furthermore, if he doesn’t give you a nice enough present this Christmas, or just continues to hack you off with his bragging about his tax breaks, you can dob him in. More on that in a minute.

It’s fine, of course, for someone to hire a spouse or other relative to work for them. But if they pay more than a reasonable amount, and Inland Revenue audits them, they could end up paying a lot more than they have saved in tax over the years.

The rules are slightly different, depending on whether the business is a company. If not, and the business owner is hiring his or her spouse or civil union partner, they must get prior approval from the IRD of the amount to be paid, says Graham Tubb, the department’s national manager, technical standards.

But regardless of the company status, if the employer is audited, the onus is on him or her to show the pay given to a relative or shareholder is reasonable for the work they do.

“We have some idea of what hours a standard business requires for, say, secretarial service, and what that’s likely to cost,” says Tubb. “And we look at the size and nature of the business and who else is involved.

“Someone has to do the books, for instance, but if they’re paying an outside accountant as well as their spouse to do the same thing, that might need some explanation.

“The department suggests that taxpayers take careful advice about the appropriate rate to pay a relative.”

If the IRD decides an employee’s pay is unreasonable, the department charges not only the tax that should have been paid but also interest, plus perhaps a late payment penalty and shortfall penalty.

That last one can be as much as one and a half times the tax due, for tax evasion — although the penalty can be reduced by up to 75 per cent if the taxpayers come clean before the IRD says it plans to investigate them, or by 40 per cent if they come clean after being told about an investigation but before it starts.

Despite the big penalties, you may well be right that thousands of New Zealanders effectively split their income by hiring family members who do little.

They should at least be smart enough to shut up about it.

“Inland Revenue is prepared to receive anonymous information regarding taxpayer activities,” the department says. “People can call the toll-free number, 0800 377 774 with information which will then be followed up.”

Telling on your family and friends is not nice. Then again, nor is their ripping off the rest of us taxpayers.

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let’s keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm is a freelance journalist, a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL), a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. From 2011 to 2019 she was a founding director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won’t publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.